For quite some time now, vampires have been high on The List of Sexy Monsters. Before Twilight and The Vampire Diaries, we had Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel. Before those we had Anne Rice’s sexy vamps, and so on all the way back to Bela Lugosi’s belief in Dracula’s sex appeal. And yet, nothing about blood-sucking monsters requires sexiness.

For quite some time now, vampires have been high on The List of Sexy Monsters. Before Twilight and The Vampire Diaries, we had Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel. Before those we had Anne Rice’s sexy vamps, and so on all the way back to Bela Lugosi’s belief in Dracula’s sex appeal. And yet, nothing about blood-sucking monsters requires sexiness.

After all, we also have Guillermo Del Toro’s vampires in The Strain (and before that, his chin-splitting additions to Blade II), and a mishmash of vampire elders from Buffy or the Underworld series. If the Cullens of Twilight and the Salvatore brothers of The Vampire Diaries are the modern-day descendants of Lugosi’s Dracula, their more obviously creepy cousins can trace their lineage back to Nosferatu.

F.W. Murnau’s 1922 film was originally intended as an adaptation of the novel Dracula, which had been published 25 years earlier. However, Murnau and his fellow German filmmakers could not secure the rights from Bram Stoker’s family. They went to the extraordinary length of changing all the characters’ names, but otherwise charged ahead with their production. Thus, instead of portraying Count Dracula, actor Max Schreck gave us Count Orlok. The Harkers became the Hutters, Van Helsing became Bulmer, and Renfield became Knock. Instead of London, the count moved to the made-up German town of Wisborg.

Shockingly, this renaming did not satisfy the Stoker estate, who ended up winning a court battle that led to nearly all prints of the fim being destroyed. A few managed to escape destruction, however, meaning we’re still able to enjoy this alternative vision of vampirism.

The basic outlines of the story are similar to Universal’s Dracula nine years later, with both movies’ plots deviating from Stoker’s novel to roughly similar degrees, but the differences in pacing and production stand out. (And, of course, Nosferatu is silent while Dracula was a relatively early talkie.)

Nosferatu manages to move both faster and slower than Universal’s Dracula. Where the Universal movie uses fairly lengthy takes in each scene, Nosferatu uses cuts more frequently, with the effect of making scenes feel like they’re moving faster than the scenes in Dracula. However, the pacing of the story itself is much slower in Nosferatu. It takes the movie longer to get to Orlok’s castle and to get back to the city, leaving the characters much less time between the count’s arrival in the city and the final confrontation. By contrast, Universal’s movie got to Lugosi announcing, “I am Dracula” by about six minutes into the movie, and most of its time is spent with the characters in London trying to figure out what’s going on.

The German film also spends more time building up parallels between Orlok and other threats from the natural world. We get meditations on Venus flytraps and microscopically vampiric organisms. Schreck’s makeup is also decidedly more animalistic than Lugosi’s. Orlok’s mouth is ratlike, his ears are pointed, and his fingernails are so long they evoke claws. He looks and acts far less human than Lugosi’s Dracula, who is at least able to put on a façade of charm and manners when it suits his purposes.

In other words, Orlok’s predatory nature is less social and more biological than Dracula’s. If both vampires were diseases, Dracula would be an STD and Orlok would be a plague carried by rats. Orlok falls into an uncanny valley where he is almost-but-not-quite human in his appearance and behavior. If he ever was human, he clearly isn’t anymore.

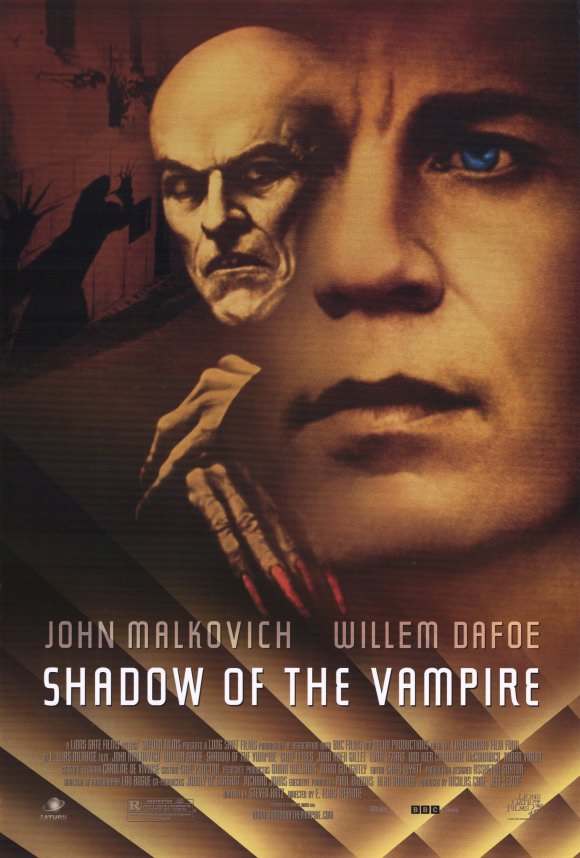

In fact, Schreck’s appearance and performance were so uncanny, they spawned an urban legend that he actually was a vampire. That provided the inspiration for 2000’s Shadow of the Vampire, which tells a fictionalized version of the production of Nosferatu where the star is in fact a vampire who has cut a deal with Murnau. The film stars John Malkovich as Murnau and Willem Dafoe as Schreck, with supporting work from Eddie Izzard, Cary Elwes, Udo Kier, and Catherine McCormack.

In fact, Schreck’s appearance and performance were so uncanny, they spawned an urban legend that he actually was a vampire. That provided the inspiration for 2000’s Shadow of the Vampire, which tells a fictionalized version of the production of Nosferatu where the star is in fact a vampire who has cut a deal with Murnau. The film stars John Malkovich as Murnau and Willem Dafoe as Schreck, with supporting work from Eddie Izzard, Cary Elwes, Udo Kier, and Catherine McCormack.

The two main draws (to me) of Shadow of the Vampire are Dafoe’s truly creepy performance and the depictions of the movie-making process. Dafoe’s performance is better seen than described, but he does a fantastic job of recreating Schreck’s movements and general aura. On the process side, the movie recreates some of the iconic moments of Nosferatu and shows some of how they were done. Watching men crank cameras while Murnau delivers real-time instructions to the actors (with no concern about competing with sounds or dialogue since this is a silent movie), and hearing Cary Elwes as a replacement photographer describe how slow-motion effects can be created, reinforce some points from my earlier post on sound in the movies. At the time these people were creating this film, they were engaging in what was essentially an enormous experiment in storytelling using a new form of photography.

Ultimately, Nosferatu has had less impact on the way we think about vampires than Universal’s Dracula did, but it did quite a bit to advance the horror movie as a general concept. From unearthly special effects – including Orlok’s straight-backed pivot up from his casket and his eventual fade-away when exposed to sunlight – to the way locations, lighting, and shot composisition created a mood, Nosferatu showed us a monster in a way that hadn’t ever been possible before.

(Images from the Internet Movie Database.)